Note:

The following article appeared originally in Dutch, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the end of WW II.

It is now translated in connection with the reopening of the restored Rijksmuseum and the subsequent series published on this website:

The ‘New’ Rijks

A Personal Tour of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

*

For five long years, Hollands’ most important museum was empty.

THE NIGHT WATCH ODYSSEY

Just before the Second World War, the world famous Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam was hastily dismantled. Some two thousand paintings, thirty thousand objects and three million prints and drawings disappeared underground.

‘Wintertime’

‘Wintertime’

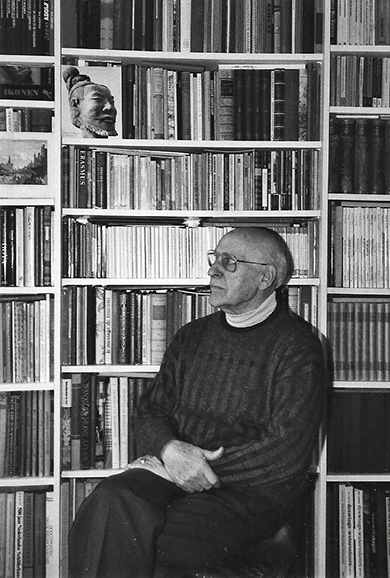

This year, 1985, is a special year for the Rijksmuseum. Not only for the centennial celebrations on the present location, but also because forty years ago its content returned home after a dramatic odyssey that lasted nearly six years. The man who was responsible during the war for the safety of that content is Mr.H.P.Baard, later the director of the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem.

In 1985, quietly sitting in his comfortable flat in Bloemendaal, it seems as if Mr.Baard has weathered the past forty-five years as gloriously as the art treasures themselves. Looking back at the high tension war years, it is mainly gratitude that remains: ‘I considered it to be a great privilege to have been in the position to do this and, as about the only one, to have remained in contact with the most splendid things that our country has produced’.

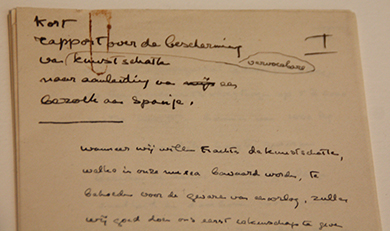

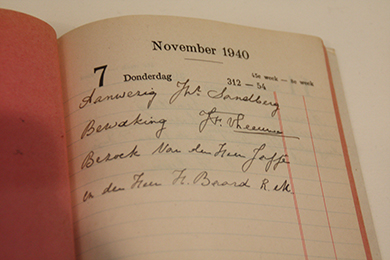

The signs of approaching evil had not escaped the eye of Dr.J.Kalf, director of the State Bureau for Monument Carei. In 1938, he produced an internal document: ‘The protection of art works against the hazards of war‘. The curator of the Stedelijk Museumii, Willem Sandberg, was on high alert as well. Spain was visited, to see how art had been protected there during the Spanish Civil War.

Subsequently, in the fall of 1939, construction began of a shelter for the city of Amsterdam in the dunes near Castricum, close to the North Sea. In the meantime, many of the city’s paintings, among them Van Goghs, were stocked in ships on Alkmaar Lake. The state government, for its part, began reinforcing the cellars of the Mauritshuis Museum in The Hague and commenced the construction of a storage facility in the vicinity of the Kröller-Müller Museum at the Veluwe, a nature reserve in the middle of the country.

The Rijksmuseum, though, proved to be hopelessly unprepared when Baard was assigned with the supervision.

Baard now: ‘At the time I was a scientific assistant at the Rijksmuseum, thirty-three years of age. But Schmidt-Degener, the director, said that I was an able organizer’. Quite a responsibility.

‘After Chamberlain’s ‘Peace For Our Time’, Baard recalls, ’the responsible minister said that the orders for sand bags and steel shutters could be cancelled, but we decided we’d better not do that’.

On August 25, 1939, the Rijksmuseum closed its doors. Shelters were not yet available, so the guiding principle became: decentralization. Spread them! In two stages, some two thousand paintings, thirty-thousand objects and three million prints and drawings, among other things, were taken to different locations north of Amsterdam. Mostly, these locations were churches or school gymnasiums.

Thus, tiny villages in the Dutch countryside were enriched with Big Art. Schagerbrug got ‘The Little Street’ by Vermeer, Wieringerwerf received a festive visit by Rembrandt’s ‘Jewish Bride’ and ‘The Merry Drinker’ by Frans Hals tried his luck in Lutjewinkel. Radboud Castle in Medemblik became the stronghold holding The Night Watch and other large pieces depicting civic militia companies. To get those huge canvases inside, the window of the castle’s Knight’s Hall had to be widened, by hacking.

Then, quiet set in, until early May 1940. Baard: ‘I had a motorbike and drove back and forth between the depots to check them. It was a wondrous experience to hold Vermeer’s Little Street in your hands without its frame and to see through the window right beside it the sheep grazing in the meadows’.

But from May 10th hell broke loose. Bombs fell and in the afternoon of May 13th it was decided to evacuate The Night Watch to the shelter in Castricum that just had been completed. Accompanied by the heavy sounds of artillery fire, the transport got underway.

The monumental painting of Captain Banningh Cocq and his company passed the night in the village of Winkel, under the overhang of a smithy, to reach Castricum the next day.

Near the bunker site the painting had to be taken out of its canvas stretcher and then rolled on a large cylinder, with the painted surface on the outside. Everything done in the open air. It was a first class operation, carried out with not even the slightest damage.

(Photo: Stedelijk Museum)

After the capitulation of The Netherlands, the ‘honeymoon tour’ of Rembrandt’s Jewish couple nearly ended in disaster. Five bombs fell just beside the depot in which also many prints and Rembrandt’s ‘The Denial of St Peter’ were kept. It prompted the transfer of the most important works to Medemblik, while the content of the State Print Room found refuge in the Baptist Church in Nieuwe Niedorp.

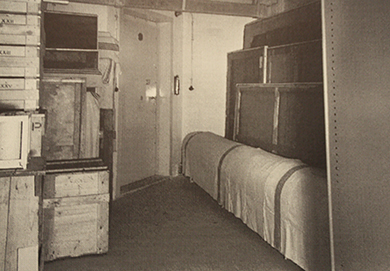

As of the early spring of 1941, two brand-new shelters became available, consisting of eight bombproof vaults under the dunes of Heemskerk and Zandvoort. On March 21, The Night Watch was brought from Castricum to the new site in Heemskerk. Subsequently, a colourful procession of treasures from Hollands most important museums found its way to a lot of protective concrete. What impressed Baard the most was the entering of the mummies, as if they were newly laid to rest in a king’s tomb.

All paintings were hung onto sliding racks, without any chronological order. Baard recalls that this ‘beau-désordre‘ resulted in a highly captivating exhibition. ‘In the museum everything is hanging so tidily next to each other, dictated by chronology, but in the shelter Charley Toorop was the neighbour of Kruseman’.

Maybe it would be an interesting suggestion to let this ‘beautiful disorder’ relive for a while?

During the severe winter of ’41-’42 a plan was made in Germany that would trigger a new major transport of the artworks. Hitler’s ‘Atlantikwall’ meant that they were anew right in harm’s way, so they had to be moved again. In record time a new vault was constructed near Maastricht, in the south of the country, exclusively for the prime pieces. The vault was positioned at a depth of thirty-five metres underground in the St. Pietersbergiii.

On March 24, 1942, The Night Watch embarked upon the fourth stage of its odyssey. Together with the other pieces it was put in lorries that were fastened upon a freight train, especially equipped for the occasion with a passenger transport chassis. The other art works were put up in facilities that were by now familiar to them: schools and churches. This time in the vicinity of Steenwijk, in the eastern province of Overijssel.

In the summer of ’42 a colossal bunker was constructed in the same area, close to the hamlet of Paasloo. This edifice arose mainly above ground, topped by a cone shaped concrete roof with a maximal thickness of nine metres. The length of all the steel used in its reinforcement equalled the distance between Steenwijk and Paris.

After the completion of this massive work a period of calm ensued.

Baard recounts meeting a farmer at Paasloo in that time, who said: ‘So, you are from the Rijksmuseum, eh? Well, I’ve been there once myself, too. There, you went into one room, and then out of the other’.

Baard, laughing: ‘That remains the best definition of a museum I’ve ever heard’

To the surprise of many, the dune bunkers were reopened in 1943 to accommodate so far unprotected items of value from several museums.

A problem in itself were the changing atmospheric conditions to which the paintings were exposed.

Baard: ‘The bunkers in the dunes were at first too wet, due to the hasty move. The still hardening concrete exuded too much moisture, even though we had installed excellent air-conditioning in all shelters’. That was certainly needed as well in the moist marl of the St.Petersberg.

During the construction of Paasloo, by contrast, fast hardening concrete was used. The air became even too dry there, up to the point that buckets of water had to be emptied onto the floor. Baard: ‘I had a very peculiar problem with a work by Dick Ket. The paint of that one was mixed with low-quality oil and it began to droop. So, I hung it upside down to reverse it’.

One of the most persistent misunderstandings is that Holland’s most important works of art were hidden from the Germans. That was not the case. ‘A secret depot was not even contemplated’, Baard asserts and a transport to England was too risky.

And yet, the question poses itself why the Germans didn’t loot these treasures. Baard: ‘In fact, although Jewish private possessions have been brought to Germany, that didn’t happen with national property. The Germans were impressed with the way how we had protected the art. Here, it was safe. Safer than in Germany itself, that was bombed. And they thought they were going to win the war anyway. Then, it wouldn’t matter much where it was. Hitler had planned to open an enormous museum after the war at Linz, where he wanted to exhibit all stolen top pieces from the conquered lands’.

Mr.Baard recalls that a bigger danger lurked because of ‘loose’ officers with private ambitions. After such a threat had once materialized, the Germans procured a document stating that any access to the shelters was forbidden without the consent of the highest authorities.

(Photo: Stedelijk Museum)

German rule, though, meant that at times highly placed visitors appeared. Especially traveling generals proved to be more interested in the bunkers themselves than in their content. One of them had himself enlightened by an ‘art loving’ major, who pointed the general to the ‘Germanic’ painter Rembrandt and the portrait of his brother: ‘That one is maybe not completely pissed, but at least half drunk’, was the aesthetic critique.

Baard: ‘The commander of the Wehrmacht was one of the few who admitted not to have any idea about art. Once, a German officer apologized for the painful situation. That was someone who I had guided through the Rijksmuseum in 1935…’

‘The most welcome guest was Plutschar, the man responsible for the so-called ‘Kultur-Schutz’iv (**). Some people of the Kultur-Schutz were very well-informed. At Paasloo they once showed up to ask where the portrait of Prince Bernhard was, painted by Queen Wilhelmina. Only very few knew of its existence’.

Sometimes, visitors of a different kind offered an opportunity for a triumph in silence. Once, Seyss-Inquartv inquired after a painting by Jan Steen. It prompted Baard to point the ‘Reichskommisar’ at the symbolism of the painting that related to fate’s fickleness. For the occasion Baard liberally translated the old title ‘So won, so consumed’ into German as ‘So gewonnen, so verloren‘, ‘So won, so lost’. That was right on the edge.

Concerning the visit of the ‘Leader’ Anton Mussertvii Baard wrote: ‘It was a piteous spectacle, to see the small man parade along our old masters, between-whiles putting up an angry little face, trying to look imposing’.

H.P.Baard now: ‘At a certain point I said to him that the visit had to end, because I had urgent matters at hand. Those matters were in fact listening to the radio, something we lived on. But I didn’t tell him that’.

As numerous as bizarre were the rumours that accompanied the cultural odyssey. So, the stock of paintings aboard ships at the Alkmaar Lake gave ground to the widespread conception that The Night Watch was kept in a zinc cylinder at the bottom of the lake. Likewise, the transport of big pieces depicting the militia to Medemblik was transformed in the public opinion as a transport of weapons and ammunition.

The liberation drew near. Baard: ‘One of the most beautiful moments of the war was the BBC broadcast after the fall of Stalingrad. Then, from between the paintings, where the radio was hidden, ‘The Gate of Kiev’ by Moussorgsky rang out. Something I’ll never forget’.

For a moment there was the fear of destruction out of rancour, but everything went well. On September 14, 1944 Maastricht was liberated. Paasloo followed on April 12, 1945. Only at the Veluwe there were some problems. During heavy fighting Canadian tanks had taken position right on top of the State art shelters.

Baard illustrates the difference in atmosphere between before and after liberation with the example of the water reservoir at Paasloo. This was meant as extinguishing water in the event of a forest fire. During the occupation a German military man had asked if it would be used to flood the shelter in case of danger, upon which Baard had to explain to him that such an operation would not be favourable for the content.

By contrast, a liberating major saw it in a more lighthearted way: ‘I thought the lake was meant for the evacuation of the goldfishes of the Royal Family’.

On June 25, two ships laden with art left Maastricht in the opposite direction. The Night Watch was on board the vessel ‘Given by God’, the skipper of whom had never even heard of Rembrandt. Due to an obstruction the ships had to sail via Belgium, where an estimate had to be given of the cargo’s value. To the astonishment of the skipper it was put at at least one billion guilders. ‘Gold by Rembrandt’, the skipper gasped in disbelief.

Simultaneously with the entrance of the Queen, the two ships sailed into jubilating Amsterdam.

After the collection at Paasloo had returned home as well, the official end of the odyssey fell on the fourteenth of July. Everything was back where it used to be, but not how it used to be. The paintings had darkened, as their varnish had not been in daylight for nearly six years. But that process was reversed by itself, with time.

Something else, though, was an interesting observation Baard made. He had the feeling the artworks had become much older than could be explained by a period of a mere five years. As if the abrupt break in history and the forced technical advances during the war had set the old works a whole period further back.

*

© 1985 Joost Overhoff

*

State Bureau for Monument Care – Today: Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands

(*) Probably this concerns the ‘Kunstschutz‘, possibly Dr. Eduard Plietzsch.

iToday: Cultural Heritage Agency of The Netherlands

iiStedelijk Museum for Modern Art, Amsterdam

iiiSt.Peter’s Mountain. (‘Mountain’ for Dutch standards, that is. Height: 107 m)

ivProbably, what is meant here is the ‘Kunstschutz’ (Art Protection). Possibly, the person meant is Dr.Eduard Plietzsch.

vArthur Seyss-Inquart, Austrian nazi commander of The Netherlands. Executed at the Nuremberg trials.

viJan van Schaffelaar, Dutch hero figure, who jumped off a tower to save his men (July 16, 1482).

viiDutch leader of the fascist party NSB. Executed at the same site where many Dutch citizens had been executed by the nazis.