Twenty-five years have passed since that unforgettable day, the day the demonstrations on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square were crushed. Until then, the square had been known mostly for being incredibly large and unheavenly ugly. After it, ‘Tiananmen’ became fixed in most minds as a historic event.

For many young Chinese it is unforgettable too, but in a different way. You cannot forget what you’ve never known. Chinese authorities have always been good at covering up, or rewriting, the past. In the digital age, that has become more difficult, but still they manage it quite well.

Digital or not, can cover-ups last for ever?

As far as they are informed about it, many Chinese now share the view that is officially held in front of them: that the crushing of the revolt was needed to avoid total chaos. Actually, that may be true. In any case, the Party has managed to remain in power all these years. Quite an achievement. For it to continue they have to go on doing what the Soviet Union failed to do: make the people richer. All the time.

Lenin, toppled

I was in Italy when Tiananmen ‘exploded’. Having studied and traveled in China in the beginning of the 80’s, even watching the drama unfold from afar left me in a state of shock.

Shocks as profound as that, like falling in love, spark writing. So, that’s what I did, now a quarter of a century ago.

RED CHINA

Il Massacro di Pechino

Rome, June 4, 1989.

I have slept badly. There was thunder in the air. And I’ve been attacked by mosqitoes. They teach you to avoid popularity: you get a lot of attention, but they eat you.

Yesterday, it was seven years since I left China. Today, it is seven years exactly since I arrived back in Europe.

I’m on holiday, or at least I try to be. Writers, reporters, are always and never on holiday. If one has eyes one is forever on duty. The only thing against it, is to close them.

A-F comes up from the landlord and his lady.

‘They’re watching ‘The Great Dictator’, she says.

We have coffee on the balcony. From a house nearby people throw furniture out of the window on a fire down below. Dark clouds of smoke envelop the dwellings of their neighbours.

We try to get organized. A-F has rented this appartment only a few days ago.

I take on the job to get the hifi working. To put it all together I need the adapter plug from the TV. In all three adapters are needed to make a working connection between the Dutch plugs and the Italian electricity grid. Europe 1989.

I try another kind of plug to revive the TV. It seems to fit and I switch on the set, expecting to see the familiar features of Charlie Chaplin.

The screen comes to light: ‘Il Massacro di Pechino‘.

I gasp for air.

Horrified, I watch the moving images and that terrible title remaining fixed on top of the screen. Il Massacro di Pechino’.

They did it! My God, they did it!

I suddenly recall one of my thoughts during sleeplessness: ‘Not on Tiananmen, ‘The Square of Heavenly Peace’. That would be too terribly ironical.

But they did do it! The ‘People’s Liberation Army’, on ‘The Square of Heavenly Peace’, between the ‘Hall of the People’ and the ‘Museum of the Revolution’, watched by Mao’s portrait – his corpse in the adjacent mausoleum – that People’s Liberation Army massacred the people.

I realize I am carried away. As a matter of fact ‘Tian-an-men’ means ‘Heavenly-Peace-Gate’, to be precise. That is the hard reality. It is only the gate to Heavenly Peace, and most probably referring exclusively to the Imperial Court that once resided inside. For ’the people’ it was forbidden to pass that gateway towards Peace. They had to endure the misery outside.

Now, that ‘Forbidden City’ is open to the public, symbolically. And a new fortress of power has emerged – symbolically? – only slightly to the west. ‘The New Forbidden City’ I always thought, while cycling past Zhongnanhai.

The Italian correspondent in Peking speaks emotionally. I can only understand half of what he says. But the word ‘Massacro‘ stays there all the time. The news ends with a short announcement of the death of Khomeiny. A major political event, turned into a side-affair.

I turn off the television and sink back in the chair, watching the dead screen, paralysed.

A-F turns up with two steaming plates with home made ‘fettuccine’, a surprise present from the landlady. Apparently the world just goes on.

I eat the pasta in the same chair, without any appetite. A major gastronomical event, turned into mere feeding. The sauce is red.

A-F asks how the Chinese drama could have happened. I speak about hawks and doves.

I go out on the balcony, unable to contribute any longer to the arrangement of the house. Everything seems senseless.

I walk up and down the balcony. The sun is shining without restraint, strikingly so, as always in the event of death. But in Italy the sun shines often and pasta sauce is often red.

Stopping at the edge of the balcony. I look down and notice that slogan again, handpainted by the landlord on a big piece of board: ‘Wine is the enemy. Who does not dare to take it on, is a coward’. It can’t make me laugh anymore.

I walk back and forth, and stop again, surveying this time the illegal housing, built all around us, wich nearly makes you forget ours was ‘wildly’ constructed too. Things come into being there where they can. History follows its course, slowly like a glacier, or thundering like a torrent.

Just this morning I read an article about the historian François Furet, who has studied the French Revolution. He doesn’t believe history is the necessary outcome of cause and consequence. I do. We are only all too limited to comprehend all the variables. That makes the work of the historian impossible from the outset. To present selective descriptions is the best he can do.

History is the result of everything. And, therefore, so are revolutions. So is Tiananmen.

I can’t keep the images from my mind of the Chinese dining halls at Peking University. Probably the worst food I’ve ever had. Communism has bred well on empty stomachs. Any revolt feeds on the lack of adequate conditions. But even if revolutions can be premeditated, ignited by an elite, they tend go their own way.

Furet’s hypothesis that wars are a flight to the fore by those who can’t control the processes they helped create, that I do believe. At least I think that is the case more often than not.

It brings the Cultural Revolution to my mind, combined with a mountain road in Switzerland: after a long downward slope, the road turns left, with straight ahead an ‘escape lane’. Platoons of oil drums at the end. The students at Tiananmen, they too set something in motion they couldn’t stop. I don’t believe there was a mastermind. It just went on as it went.

My God, what a tragedy! China wants to modernize, but both the leaders and the students forgot to study history. The leaders didn’t learn from the past that modernisation, and the opening up towards the outside world, would inevitably lead to changes in society, other than purely economic. Like Japan, they have tried it before, to change one thing and attempting to freeze the other, with disastrous results.

They are trying it again. This leadership is too old. They cannot make the second change. They have rejuvinated the institutions but are not prepared to go themselves. But, my word!, how scary it must be for any rigid system that has altered its course, to change ships when already in the rapids. And it’s not easy for revolutionaries to accept, that once they have petrified while in power their immobility makes them counter-revolutionary.

A-F and I have dined one of these days with a friend of hers, a psychoanalyst. We talked about the relations between doctor and patient, and we spotted similarities with the bonds between parents and children, between rulers and the people. For the doctor, for the parent and for the ruler to say ‘You need me’ is another way of saying ‘I need you’.

They need you

The students, yes, they want to be modern, but they have neglected the classics. Why did they press on, unrelenting? Ancient Chinese wisdom could have learned them the virtues of, temporary, retreat. Were they afraid to let go again, in fear of a more silent repression? Did they misjudge the tenacity of the tree they tried to uproot by pushing only? Was it just an irrational euphoria of ‘now or never’?

Again, I walk up and down the balcony to halt at the same spot. This time I see the eucalyptus trees. They are dying. Only yesterday the landlord explained to me that eucalyptus somehow keeps the mosquito population down.

‘But they are dying’, I said.

The little old man pointed at a tree that still appeared to be relatively healthy.

‘Only one is enough’.

Yesterday, I read a phrase of the editor of the Soviet periodical Ogonyok: “Some people see the holes in the cheese, others see the cheese around the hole”.

Am I a pessimist? Or only now?

Two days ago we tried to buy a steel coffee pot.

‘This aluminium one is the best’, the woman said.

‘But it is bad for your health’, we countered.

She looked pensively.

‘Ah, but you should drink the coffee directly when it’s made!’

It is not easy to get a message across to the masses. If that was tried somewhere, it certainly was tried in China. They have tried, for instance, to crush Confucianism and folk beliefs. It didn’t work. They were too deeply rooted.

Often they have tried to convert, to persuade, rather than to kill political opponents. Deng Xiaoping is the living proof.

‘Xiao-ping‘, ‘Small-peace’. My Goodness! And Li Peng!, related to Zhou Enlai, for Heaven’s sake. Zhou Enlai, the only genuinely loved statesman of the communist era. And this Li Peng murders the people. Zhou’s people.

Am I carried away again? Where, in fact, does murdering ‘people’ stop and does murdering ’the people’ begin? Where is the dividing line between ‘subversion against the state’ and ‘subversion by the state against the people’? Objectively speaking, for what that’s worth. Is it a question of numbers of demonstrators?

Mr.Andreotti, the Italian mimister of Foreign Affairs says on television: ‘Well, if two out of every hundred Chinese would take to the streets you have a crowd of over 20 million”.

Yes, but if a million people take to the streets in Peking, you speak about one out of eight.

Of course, revolutions don’t follow a ‘pure’ course, and neither do masses consist entirely of people with the same intentions. Idealists are joined by the curious, by those who are glad to have a day off, by others. But the less so when there is danger in the air.

Or is it just the general feeling that a government has lost its basis in society that makes the acts of a state subversive?

The Chinese word ‘ge-ming’ for ‘revolution’ is fascinating. It means in origin: ‘changing the mandate’, referring to the so-called ‘Mandate of Heaven” of which the Emperor was supposed to be the bearer. Certain signs, natural disasters for example, could point to the imperial loss of its Mandate and, so, justify the overthrow.

The students tried to ‘change the mandate’, and uniquely so by peaceful means, but the rotten tooth still held out. The thought of the eventuality that it might not have held out, had the people alternated advance and retreat, is nearly too much too bear.

Strange, comparisons have been made between these demonstrations and those of May 1919. Then, the protest was ignited by the Treaty of Versailles that ‘sold out’ parts of China to foreign countries. Clear proof that politics have everything to do with interests and nothing with justice, or only if it suits the interests.

What will the international community do now? The first signs are not encouraging. The game is still the same. China wasn’t heavily criticized for supporting Pol Pot, we even supported him indirectly ourselves. So why would the West care about a few thousand massacred, if it didn’t care about a few million? If it doesn’t suit its interests.

Why has China so often been protected by the aura of the exotic? Why have similar wrongdoings in the Soviet Union always been criticized and those in China overlooked? Because the Chinese look different? So that we think that makes them different too? To a point that it also puts them in a different category of ’the ones we don’t understand’, leaving us without criteria to judge them?

If we make comparisons, will the current repression with its initial ‘success’, prove to be the overture to the downfall of the old guard? Like the Boxer uprising of 1900, a last stupor?

That one too, was a desperate attempt to try to turn the tide. It was a popular revolt against western influence, supported by the Chinese leaders. The Cultural Revolution was a popular movement too, but instigated from above, and now: the army against the people. Three different situations with one common trait: the struggle to retain power at all costs.

And Khomeiny dead! What a day! He proves that sometimes only death can pave the way for spring. And that, eventually, it will.

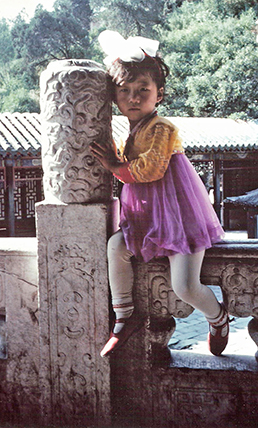

I keep walking up and down the balcony and stop this time in the middle, to lean over the railing. I watch the backs of two small stone lions that guard the entrance to our ten yard driveway, and the copies of Roman deities that always survey the movements of our landlord’s minuscule Fiat.

I am on holiday, and I study the Greek classics, long after having studied the Chinese ones. The far away always seems more attractive, initially. But why the classics, when we have our own tragedies around us?

And, still, the classics are priceless. We should study them even better. Because why, why did I think: ‘They won’t do it, they just can’t. In our age such a thing is no longer possible. Unacceptable’? Why was I so naive to suppose that millennia of atrocities would just stop here?

We should have studied Thucydides and Chuangzi, who both lived some one and a half thousand years ago. Thucydides, the Greek historian, already prophesied that the events he described would be repeated in the future “human nature being what it is”.

And Chuangzi, follower of the great Laozi, already knew that ‘when animals face death, they don’t care what noises they make’. These men already warned us. But we only looked at the present, with ill-founded hope.

Also, Thucydides’ breathtaking account on revolutions hasn’t lost anything of its actuality. He already noticed that “to fit in with the change of events, words, too, had to change their usual meanings”.

My God, isn’t the term ‘counter-revolutionary’ the most abused one of this century? The modern heresy.

I watch the sky. It looks Italian. It is Italian. How far I am from China, in distance and in years. And yet how close.

Italy. What reminds of China here? Marco Polo, yes, the merchant whose account on the ‘Middle Kingdom’ has dominated Europe’s view of China for such a long time.

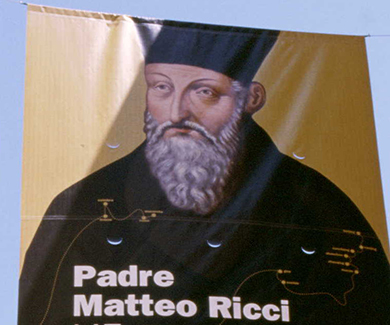

What else? Let’s see. Yes, Matteo Ricci and Giuseppe Castiglione, the two great Jesuit scholars who reached high status at Chinese courts.

That’s about it. But no, of course, Machiavelli! How could I forget him. He reminds very much of China. His ideas bear a striking resemblance with those of Han Feizi, the Chinese legalist thinker.

Machiavelli would have praised many Chinese leaderships. But not this one. Because they waited too long. Machiavelli taught to tackle a problem straight away, before it grows too big.

Why did they wait? Because there was no coherent leadership? Because they simply didn’t know what to do? That was both so frightening and fascinating about the silence from ‘above’: the apparent struggle for power, to acquire the right to define either black or white as ‘counter-revolutionary’. Those moments in the eye of the hurricane, when both fears and ambitions keep each other for a moment in the balance, making people uncertain what side to join. Moments, so abundant in the accounts of Thucydides.

And Machiavelli has proven right on more points. He advised either to caress or to destroy one’s enemies, because the wounded are likely to seek revenge.

That was exactly what happened: the students used Gorbatchov as a shield, making it impossible to be destroyed, at that moment; unable themselves to destroy their rulers, but wounding them deeply, through grave loss of face. And so, the shield became a boomerang of revenge. The man from Florence already warned that ‘it is not likely that someone who is armed will obey someone who is not’. Hawks tend to kill doves.

But then they had to decide how to do it. To murder the protest leaders only, or to kill indiscriminately. Like the ‘Mytilenian Debate’. Was the outcome that close again this time?

Why didn’t they use teargas? Why? To make a greater impression? To get rid of as many of them as possible?

Possibly, or probabably even, both students and leaders didn’t follow any great lines of thinking. More likely they acted haphazardly, swirling into the tragedy in a whirlwind of hopes, bewilderedness, indecisiveness and ambitions.

Machiavelli noted as well that most rulers are bound to fall because they cannot keep up with the times, especially if certain lines of conduct served them well in the past. Will we ever know how close the Chinese rulers were from falling at this point?

Believe it or not, we have to leave for the tennis club. A-F has to play for the club championships. It seems all too ridiculous, today.

At the club, though, nobody seems to be concerned about anything. It gets close to being hallucinating. People eat ice creams next to the pool.

‘Chi ku‘, ’to eat bitterness’, that is what the Chinese do, while the atmosphere around the court breathes a sunday afternoon party.

To my mind comes the face of a young woman I met at a party in Peking.

‘It is so terrible to live within this system’, she said. ‘I can’t bear it anymore. I don’t think I will live much longer…’

The most impressive line in the Dutch language is so hard to translate: “What is of value, is without defense”.

The night is dark. But Laozi taught us: ‘Darkness is what the light needs, to be seen’.

*

© Joost Overhoff