It happened only recently. Suddenly, a book title reappeared in my head. Like an archaeological artifact, after a long time coming to the surface, there it was:

‘The walls came tumbling down’

The first time I became aware of that book dates back nearly half a century. In between studies, high school and university, I ended up in the French Alps. To learn French, to go skiing and to have a good time.

At the language school, there was an abundance of Dutch girls. And just one boy. Me.

But I wasn’t the only rare bird around. There was Yet, too.

Yet was… an heir, in the midst of a group of school-leavers who were too young to inherit anything, if there ever would be anything to inherit. But, even though someone might be too young to inherit, testators can die early, or they can belong to earlier generations. That’s what happened to Yet.

Yet was the heir of… Yet. That way, ‘young Yet’ came in possession of the house that ‘old Yet’ bequeathed to her, even though old Yet hadn’t grown old.

Yet’s house happened to stand in France, not far from our Dutch ‘colony’. So, what did we do, we lowland colonists? Right. We went there, the whole bunch.

Old Yet’s house, by contrast, turned out to be really old. It still contained many things that had belonged to young Yet’s late aunt. Among all those things was a book, written by old Yet herself. It was about her journey right through the chaotic end of the Second World War, after being released from a far away German jail. After

‘The walls came tumbling

down‘.

But was I going to read that book? Certainly not. We were living in the present. So it happened, that in the little village there was another writer to be found. Someone who was still alive and we were all familiar with because of the reading we had done for our high school exams. That writer, Gerard Reve, dwelled nearby with one of his same-sex lovers, and we were more eager to catch a glimpse of that pair than to embark on reading an ‘old’ book.

*

After that French period we each went our separate ways and decades passed. My own father died too. Like old Yet, he had experienced ’the walls tumbling down’. In his case that happened much further away, in today’s Ukraine. Never, though, had he given us a detailed account of how that happened, and how he made his way back home. But I remember acutely that the experience gave him a lifelong wariness of the Russians. Of his liberators! That greatly puzzled me.

Only long after his death, a fellow prisoner of war recounted that people among the local population had killed their own daughters, to spare them the Russians.

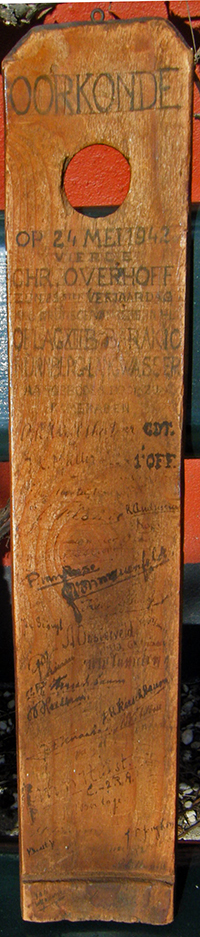

(24th of May, 1942)

Back to recently. When, after all that time. the ‘Walls’ had entered my head again, things went quickly. I was now ready to read about that forgotten part of history, as if it were a WWII-footnote. An epic epilogue.

How had it been, the journey back, heading home right through the land of the beaten enemy? While you may have dreamed that, as the main gate creaked open, a limousine would be standing there, a spacious car with chauffeur that would drive you to a balcony in the motherland, under which an endless crowd would be cheering at you…

I now wanted that book, and more than that, I wanted it right away.

I turned to an online bookseller, bol.com, not expecting to still find it in a regular store.

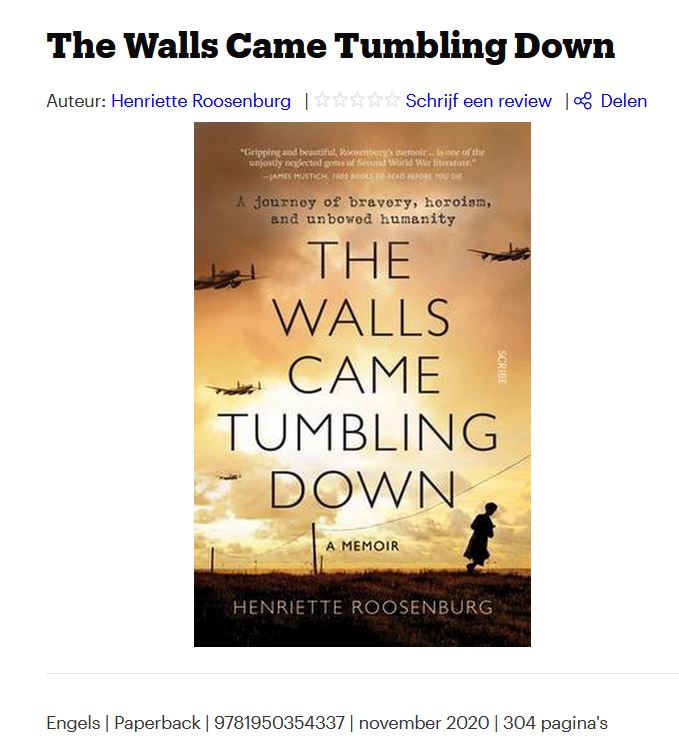

It was a direct hit. The cover appeared instantly on my screen, the cover of a paperback, complete with a somewhat roaring ‘surtitle’.

But was this version the original one? Had Dutch ‘old Yet’ written her book in English?

Who would know that better than young Yet? But how could I find her? Via Google.

Within moments I found what I wanted. The house she had inherited proved to have been made into a Bed & Breakfast, at which an email address was beckoning invitingly.

Said, done, contact restored. So I learned that the English version of ‘The Walls’ had indeed been the first one to see the light. Only later had it been translated into Dutch by someone else, and now revised for a recent fresh release.

Good, but that wasn’t the version that I was looking for. Once more, I turned to bol.com. There, the paperback was still for sale, for a price I was prepared to pay, and nearly did, when I noticed that lower down it stated, in tiny letters, that there were two more offers of the same book. Additional clicking revealed that one of them was much cheaper. Well, I thought, if it has to be a paperback anyway, why not?

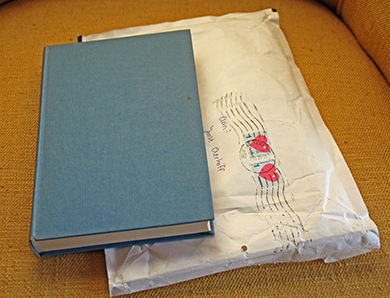

With improbable speed I found a white envelope in my letterbox. I opened it with anticipation, even though I already knew what it was. I thought.

But no. I couldn’t suppress a cry of surprise. The envelope contained something completely different than what I thought I had ordered. The book’s cover was blank. Only a celestial blue stared at me, that what you dream of in a dark prison cell.

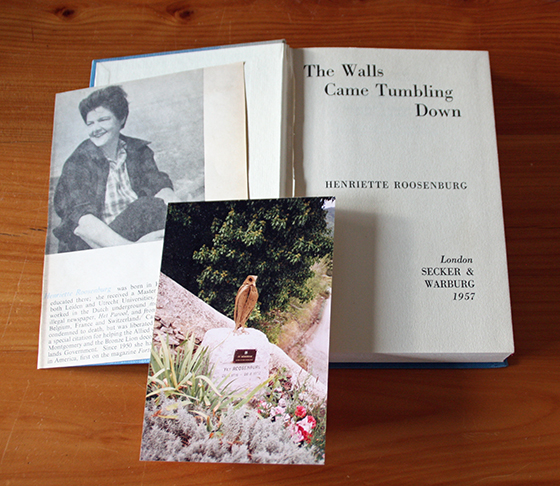

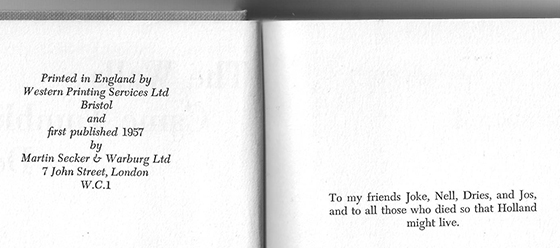

It was a hardback. And not only that. It was the first English edition, from Secker & Warburg. That didn’t complete the surprises, though. Opening it, I found the book to be both enriched and impoverished: two things were added, while something else was missing.

Inside lay a clipping, underneath it a photograph.

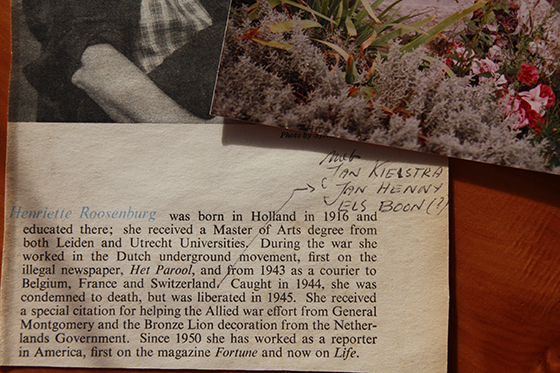

The clipping showed a picture of the old Yet, dating from, yes, from when? Around ’57? The accompanying text revealed that she had started her ‘illegal’ activities at the resistance publication Het Parool (The Motto, being ‘Free, fearless’). Founded in 1940, it happens to be the same paper that I began to write for myself, some forty years later.

Later during the war, the clipping stated, Yet had run courier services for the resistance to several countries. A handwritten addition in Dutch added that she did so together with three others, whose names were spelled out.

The clipping continued to note that Roosenburg had been awarded with a Dutch Bronze Lion and a ‘special mention’ by General Montgomery. From 1950 onwards she worked in America, first for the magazine Fortune, then for Life, that I vividly remembered from my childhood for its great pictures.

The loose picture in the book, by contrast, was made by an amateur. It seemed to be a shot of old Yet’s grave. In France?

It suggested that the book’s owner had known her personally, or at least had heard of her and admired her. So much so, that he had undertaken the voyage to her grave site.

In any case it felt as if, by choosing the cheapest option, I had won a sort of jackpot. Not completely, though. The flyleaf was cut out of the book. Possibly, probably, with a dedication. From the author to the owner of her ‘Walls’?

My attention shifted to the book’s seller. Was it a private person, or a trader? Had that person noticed that something had been hidden inside that book?

I returned to the bol.com website and looked for a possibility to get in contact with the seller. To no avail. It seemed to be a woman, judging by the fact that the seller used a female first name, followed by a number.

A chat with bol.com made clear that a contact possibility should have been there, so the fact that it was lacking indicated that the seller didn’t want any feedback from the buyer.

Not giving up, I asked my chat contact if she couldn’t send a message to the seller on my behalf.

And, lo and behold, not much later I received a message from the seller via bol.com: the book had been owned by a certain Pierre d’Aulnis and had ended up in an inheritance through a connection by marriage. ‘I saw the photo and the clipping and left them there on purpose. Unfortunately I don’t know anything more‘.

Google-time, again. Who had been this Pierre d’Aulnis? Another resistance fighter, it appeared. A very adventurous one at that. And persistent: as he didn’t receive the Netherlands’ highest honour, the Military William Order, he applied for one. And got it.

Yes, medals… It’s good they’re there, but they are like life itself: they aren’t proof of automatic justice. Too many never receive one, others receive too many, and some have to return one that they deserved.

In the mean time, one of the names that were scribbled on the clipping, supposedly by Pierre, kept me busy. That surname looked familiar.

It was the same surname as that of a girl of my age in the village where I grew up. By chance, I recently had gotten in touch with her again, because of an article about her in… Het Parool. It turned out that she had had her office for years in the building next to the one in which I live.

I now mailed her asking if she knew anything about the name on the clipping. To which which she replied, instantly: ‘That was my father!’

A back-and-forth mail tornado ensued, revealing among other things that Pierre d’Aulnis was called by her Uncle Louis and often came to visit her parents. Moreover:

‘I just dived into the short biography that my father left to me about his war years. And yes, just what I thought after letting that name sink in, he knew Jet Roosenburg’.

Yet’s Y probably was of a later date, to accommodate English and French speakers. Her book showed her full, official name: Henriette Roosenburg.

Meanwhile I had exchanged my ‘book-for-in-bed’ by The Walls. I couldn’t wait, even though I began reading it anxiously, fearful to turn a page which back side could reveal some horror that could befall the narrator. Even though that horror would now be part of the distant past.

As could be expected, the story begins where other books about the war end, but it is surprising all the same. In this book the captivity until liberation is just the introduction. The terror behind the prison bars is only the subject of the preface.

Again, I searched my bol-account, hunting for a lead that might lead to the seller. Nothing. Until, suddenly, above the regular section of the page, my eye fell on the address bar. There, it seemed, between all kinds of codes, also appeared what looked like the seller’s last name.

I turned to Google, once more, getting a new instant hit. It proved to be a woman in the board of a large company. That is, if there wasn’t anyone else with that name, someone the search engine was unaware of. What the devilish/godly machine did know, though, was that another company had merged into hers, a company that had employed my father too.

Well, why not? That detail could be added to the story fittingly. I was beginning to feel as if it would be only really startling if something would come up that wasn’t surprising.

I asked a new chat contact at bol.com if she would be willing to send my email address to the seller. And, yes, not long afterwards I received a direct email from the woman whose name was the same as the one I had found in bol’s address bar.

In my answer I thanked her again for the enclosures and asked if she knew anything about the cut out flyleaf. Not that I expected much. Probably, it had vanished before the book ended up in her custody. And, for that matter, was it anything of my business what had been written on that page? No, but still, I was curious to know it nonetheless.

Every evening I continued reading in ‘The Walls’. After the breathtaking liberation night, the journey home was beginning. A journey that would short-circuit the brains of any carrier pigeon. As the carrier crow flies? On the contrary. And all that in the condition they were in. While pillaging their ex-prison they had found a scale that produced a uniform conclusion: hunger had robbed them of a third of their body weight. Moreover, their time in prison may have had produced callus on their souls, but not under their feet.

‘They’ were three women, a trio that became a quartet by the added company of a Dutch seaman. A certain reassurance, one would think, but only relatively so. With surprising openness for that time, the author reveals that they were so weakened that their bodies had inactivated all secondary functions: female cycles had stopped and the seaman’s pride was no longer any match for gravity. Not quite an indication of great worth as a body guard.

The greatest threat comes from the Russians, in line with what my father’s fellow POW had told me. Their rape rage, Yet learned, was only halted if the victim, by the sheer number and roughness of the soldiers who went before them, had become ‘inaccessible’.

One could be inclined to think that the rapists would have a preference for the relatively well-fed local population, instead of ravaging emaciated allies. But that ‘sitting room-logic’ was by no means a guarantee.

To be fair: Yet doesn’t omit suspecting that occupying armies roughly behave in a similar way. Besides, she recounts that a Russian officer executes two subordinates on the spot for a rape orgy.

That, though, doesn’t alleviate the sense of threat as the foursome make their way through a setting full of soldiers, ex-POW’s, ex-forced labourers, magically-instant-ex-nazi’s, and what have you.

What is needed to make it to the end of such an odyssey? Perseverance, luck, inventiveness. And guts. all that, while the journey offers countless literal and figurative exits that could be fatal if you choose the wrong one.

And, I confess: while reading about their return, a tear came rolling down.

*

Miscellaneous

– Joke (pronounce ‘Yo-kuh’), one of the three women, is still alive. I plan to meet her.

Update: I have met her, in the late spring of 2021. At 98, she is still razor sharp. An account of our meeting is only available in Dutch.

Update: planning to meet her again, Joke died on December, 11, 2022.

– I am also set to meet the, now retired, ‘girl from my village’. She is a great-grandchild of Maria Montessori’s.

Update: I met her, too.

– Her father, Jan Henny, was awarded with a Dutch Bronze Lion, as was Yet.

– I didn’t hear anymore from the seller of the book.

– The author died in style: behind her typewriter.

– Young Yet, Yet de Villeneuve, lives in her inherited house near the route of an upcoming cycling trip.

– The book was re-released in Dutch in 2020 and published in Italian in 2021.

– It will be re-published in English, both in print and as an e-book, as of March 30, 2021 by Scribe Publications.

– Meanwhile, even a German version has appeared.

*

© Joost Overhoff