Film review

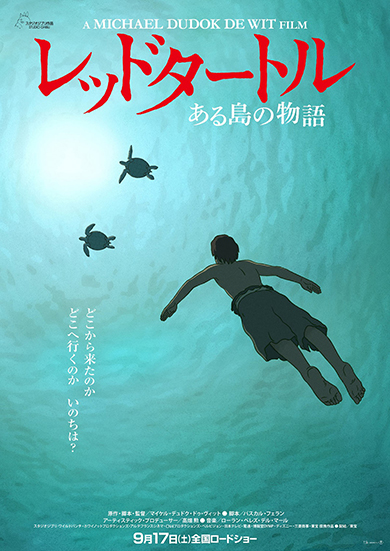

THE RED TURTLE

An animation film by Michael Dudok de Wit

When going to see a film one’s own feelings tend to ‘get in the way’, as you are always accompanied by yourself. Although those ‘own feelings’ are precisely what made you go in the first place, they can lead to interpretations that may cause the maker of that film explode with laughter, either because he intended something completely different, or, perhaps, he didn’t mean anything while creating what he did.

In this case I happen to know the maker of the film on review (see below), but not well enough to know what he means.

To the point:

How is The Red Turtle?

Wonder-full !

A few comments, though.

The ‘Turtle’ reminds me of something I have written before on a museum in Porto. ‘Serralves’ is of such beauty that one craves for it to be exhibited once just by itself, empty. Maybe forever. That museum just doesn’t need any other art. It even disturbs.

The Red Turtle is like that, too. Much of it is so beautiful that you would want the screen to freeze now and then, for ten minutes or so. And you would want it to be stripped of human characters, of a plot. All ballast overboard.

Just watch the skies… Breathtaking. The bamboo forest… A drop of water, falling… Water, receding in the sand of the beach, as a dissolving shadow, when a wave returns to sea…

The setting has in fact the lead role. The human figures appear amidst this beauty as rather imperfect, also more banally drawn intruders. Not yet Disney-like, but even so.

It is a contrast that was absent in the Turtle’s predecessor ‘Father and Daughter’. But its presence in The Red Turtle is realistic in the sense that humans, more or less coarsely, increasingly do intrude into nature. And, surely, wanting to sell a film without a plot is about as unrealistic as the continued existence of an empty museum. As a matter of fact, the viewer may consider himself lucky that the Turtle has made it to the screen devoid of any dialogue. Even though it is astounding that a textless film proves to be convincing all the same, in the Turtle’s case you even think that any spoken word would have been too much.

The dividing line between reality and fantasy, by the way, is fascinating. For example, the viewer cannot but wonder if the transformation of a turtle into a woman is fantasy, or not. Thereby, implicitly, accepting the rest of this dreamt up story as ‘real’.’

‘My own feeling’, there it pops up once more, although it is ‘his film’. But there is no escaping. So, a crucial part of the plot directs me to my own motto

‘Be where you are’.

There is no need to go anywhere. Everything is already there where you are.

In The Red Turtle a man tries to escape from the island where he is stranded and builds for that purpose ever bigger rafts. In vain. His attempts to no longer be where he is, are thwarted time and again by a huge turtle. And still, in the end, that turtle secures his happiness.

I know a Chinese man, whose wife had trouble being where she was. He said: ‘The best way I can help her is by not helping her’. That proved helpful in perceiving ‘Be where you are’.

Another observation concerns the ‘western-romantic’ soundtrack of the film, that at times flirts dangerously with becoming pathetic. Which immediately confronts one with the question of what might have been better. Although The Red Turtle is mainly Made in France, it is in essence a Japanese production. So, maybe sounds from there? Bamboo flute? Or something completely different, something new? Easier said than done.

The fact that the Japanese are especially attracted to Dudok de Wit’s work, is hardly surprising. Japan, the land of haiku, of the art of leaving out the superfluous.

Michael’s work has the same quality as the folding screen by Mochizuki Gyokusen in the Rijksmuseum. While you see dry snow sliding off a tree, you can hear that snow. At such a level a plot is no longer needed. When the soundless speaks. And if it doesn’t, that, too, will do.

Michael Dudok de Wit was a classmate of mine at high school and ‘my’ illustrator at the school magazine that I headed for a while. But Michael’s drawing didn’t stop there, it didn’t stop anywhere. Ever. He thereby gave the impression that the subject matter in class didn’t matter. Michael found himself in his own world, that accompanied him wherever he went. So, while the teacher dwelled on Pythagoras, ‘an early Michael’ was taking shape.

© Michael Dudok de Wit

I myself did’t accompany Michael that much. Although we lived in the same village, we cycled to our far away school via different routes. Michael’s led him over a long straight dyke, with a matching, typically Dutch landscape. It became a source of inspiration that is reflected in ‘Father and Daughter’, the short animation film that was awarded with an Oscar.

After school we met once more, in Geneva, where Michael attended the art academy. There, it also became clear that his artist’s imagination made him do things like attempting to ‘fly’, even though he had never been a sporting type. Although his parachute jump ended with a complicated leg fracture, it sure was proof that the artist would not shrink from a daring endeavour. An indispensable quality to complete a full-length animation film like The Red Turtle.

Although ‘Hollywoodian’ blockbusters are competing for it too, it would hardly be a surprise if the Oscar already on the mantlepiece got company.